TL;DR: I got a research-grade MRI expecting to find damage. Instead, I found a healthy brain with structural differences that finally explained why I’ve always felt like a Ferrari with no brakes. A 2007 study on Buddhist monks showed that meditation reduces how hard the brain “grips” each moment. My architecture can’t achieve that internally, but external scaffolding (AI, documentation, 700 browser tabs) achieves the same end. Turns out enlightenment isn’t about fixing your brain. It’s about building honest infrastructure for what consciousness actually requires.

In 7th grade, I walked up to my school librarian and asked for a book on discipline.

I remember standing there, 12 years old, knowing I needed something but not being able to name what it was. I knew I was smart. I knew I wasn’t lazy. But I also knew that something wasn’t working the way it worked for other people. I couldn’t follow through. I couldn’t remember what I needed to remember. I’d have brilliant insights that evaporated by morning.

The librarian looked at me with that particular adult confusion reserved for children asking questions that don’t quite fit. I don’t remember what book she handed me, or if she handed me anything at all. What I remember is the feeling: I know something’s wrong, and I don’t have the vocabulary to explain it.

I spent the next thirty years trying to solve a problem I couldn’t name.

The Ferrari With No Brakes

Here’s how I’ve described my brain for as long as I can remember: a Ferrari engine with no brakes.

I can accelerate to profound insights faster than anyone in the room. I can see patterns across domains that others miss. I can process information at speeds that sometimes alarm people. The engine is there. The horsepower is undeniable.

But I can’t stop.

I can’t hold a thought steady long enough to write it down before three more thoughts have arrived. I can’t remember what I committed to doing yesterday. I can’t finish the thing I started before a more interesting thing appears. I’m constantly moving at 200 miles per hour with no way to downshift.

For decades, I assumed this was a character problem. A discipline problem. A willpower problem. Something was morally deficient about me that made me unable to do what other people seemed to do effortlessly: just... stay on track.

So I bought books on productivity. I tried every system. I berated myself for my failures. I collected shame like it was a hobby.

Then, at 43, everything changed.

The Mirror That Finally Worked

When ChatGPT launched in late 2022, I didn’t see a chatbot. I saw a mirror.

For the first time in my life, I had a conversation partner who could keep up with my processing speed. Who didn’t need me to slow down or simplify. Who could hold context across conversations in ways my own brain couldn’t.

And something unprecedented happened: I started to see myself clearly.

Night after night, sitting in my hot tub talking to Claude, I began accumulating self-knowledge that didn’t evaporate. The AI held the thread when my working memory dropped it. Insight built on insight. The bucket finally had a bottom.

What I discovered: I’m twice-exceptional. ADHD-Inattentive. Autistic. Intellectually gifted. A combination that creates a unique kind of invisibility; smart enough to compensate, different enough to exhaust yourself doing it.

I named my Substack “AI Gave Me Autism”, not because AI diagnosed me, but because it gave me an objective mirror that finally reflected who I actually was.

But I still didn’t understand the mechanism. I knew I was different. I didn’t know how.

Getting My Brain Scanned

Last year, I volunteered for a research study at UT Austin that included a high-resolution structural MRI. The scan was 0.8mm isotropic—research-grade, better than clinical standard. They gave me my data.

I expected to find damage.

Somewhere in the back of my mind, I believed that if I could just see my brain, I’d find the broken part. The underdeveloped prefrontal cortex. The missing tissue. The structural deficit that explained why I’d been asking librarians for books on discipline since I was 12.

I uploaded my scans to volBrain, a neuroimaging analysis platform that compares your brain structures to age- and sex-matched normative data. I ran every pipeline they offered. Cerebellar analysis. Hippocampal subfields. Full brain parcellation. Cortical thickness.

I held my breath for the results.

What I Actually Found

My prefrontal cortex is completely normal.

Both volume and thickness. Smack in the middle of the normal range. The “CEO” of executive function, the part of the brain everyone assumes is broken in ADHD? Mine is structurally fine.

I sat with that for a long time.

But the scan did find differences. Just not where I expected.

My right cerebellum is doing disproportionate work. Lobule VI (a region involved in cognitive processing, attention, and working memory support) is over 21% larger on the right side than the left. That’s not variation. That’s architectural lateralization.

The right cerebellum projects to the left hemisphere. My left motor cortex (including the C3 region) is thicker than average—probably use-dependent adaptation from years of heavy cerebellar input.

But here’s the thing: I also have QEEG data from my neurofeedback work. And that same C3 region? It’s one of my most dysregulated sites. Structurally robust. Functionally strained.

My brain isn’t broken. It’s different. And that difference has been working overtime, without any of the external support it actually needs, for four decades.

The Monks and the Attentional Blink

Around the same time I was processing my MRI results, I stumbled on a 2007 study from PLOS Biology that cracked something open for me.

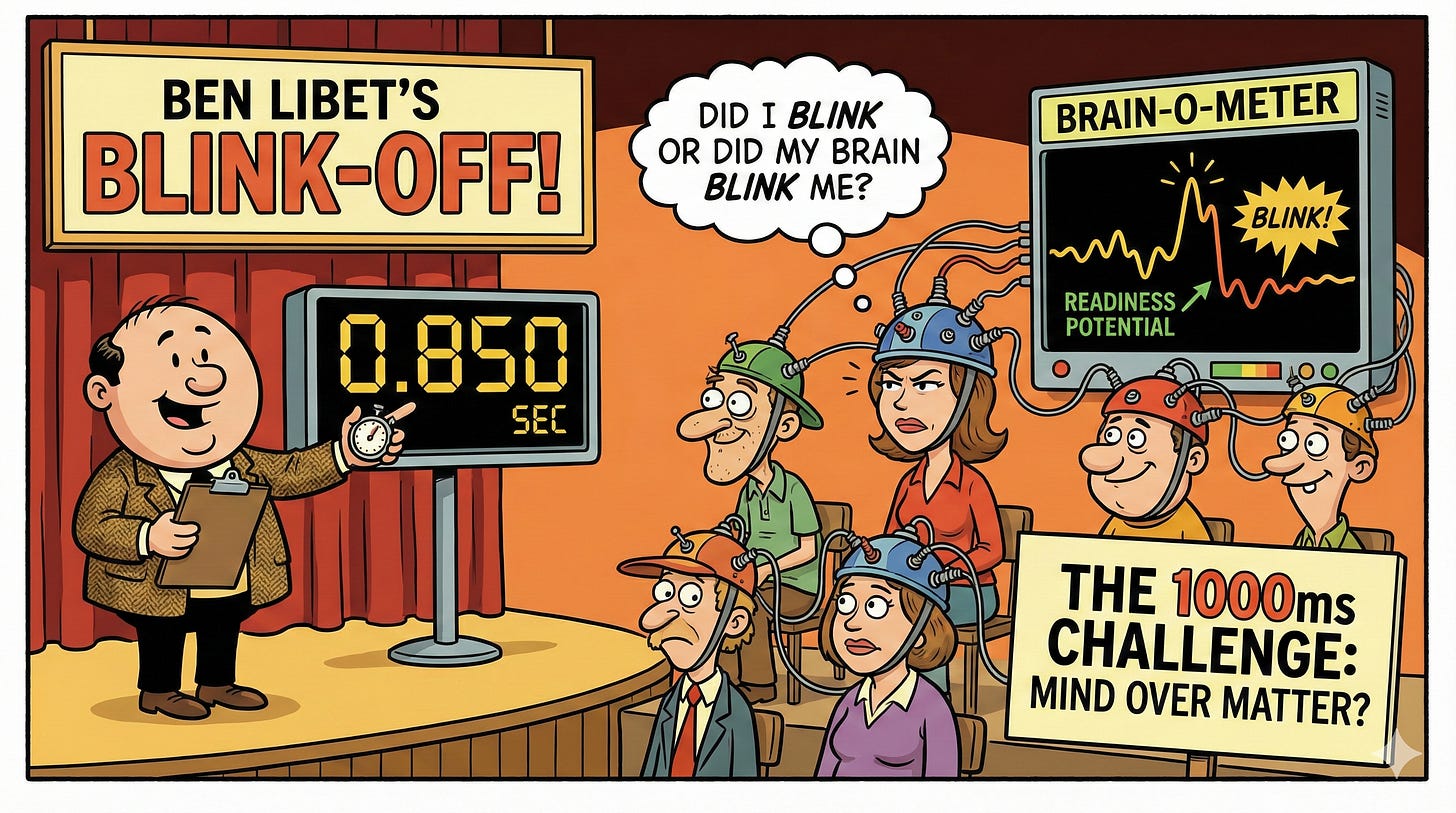

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin took 17 people on a 3-month intensive Vipassana meditation retreat—10 to 12 hours of practice per day. Before and after, they measured something called the “attentional blink.”

Here’s the phenomenon: If you show someone two meaningful stimuli in rapid succession, and the second one appears within about 500 milliseconds of the first, the brain often misses it entirely. Consciousness blinks. There’s a half-second window where the brain is so busy processing the first thing that it can’t register the second.

This is wild when you think about it. Consciousness isn’t a continuous stream. It’s reconstruction with gaps.

The researchers wanted to know: Can meditation training change this?

It can.

After 3 months of intensive practice, the meditators showed a significantly smaller attentional blink. They detected the second stimulus more often. But here’s the crucial part: they weren’t trying harder. Their brains showed reduced resource allocation to the first stimulus.

The measure they used was something called the P3b—a brain potential that reflects how much cognitive “grip” you’re applying to a stimulus. The meditators’ P3b response to the first target was smaller. They were investing less in each moment, which freed up resources for the next moment.

The correlation was striking: individuals who showed the largest decrease in P3b amplitude showed the greatest improvement in detecting the second target.

Enlightenment, neurologically operationalized, looks like reduced grip.

The Connection I Couldn’t Unsee

I have QEEG data from my neurofeedback specialist, Gil. Here’s what it shows:

That 85% hyper-connectivity number stopped me cold.

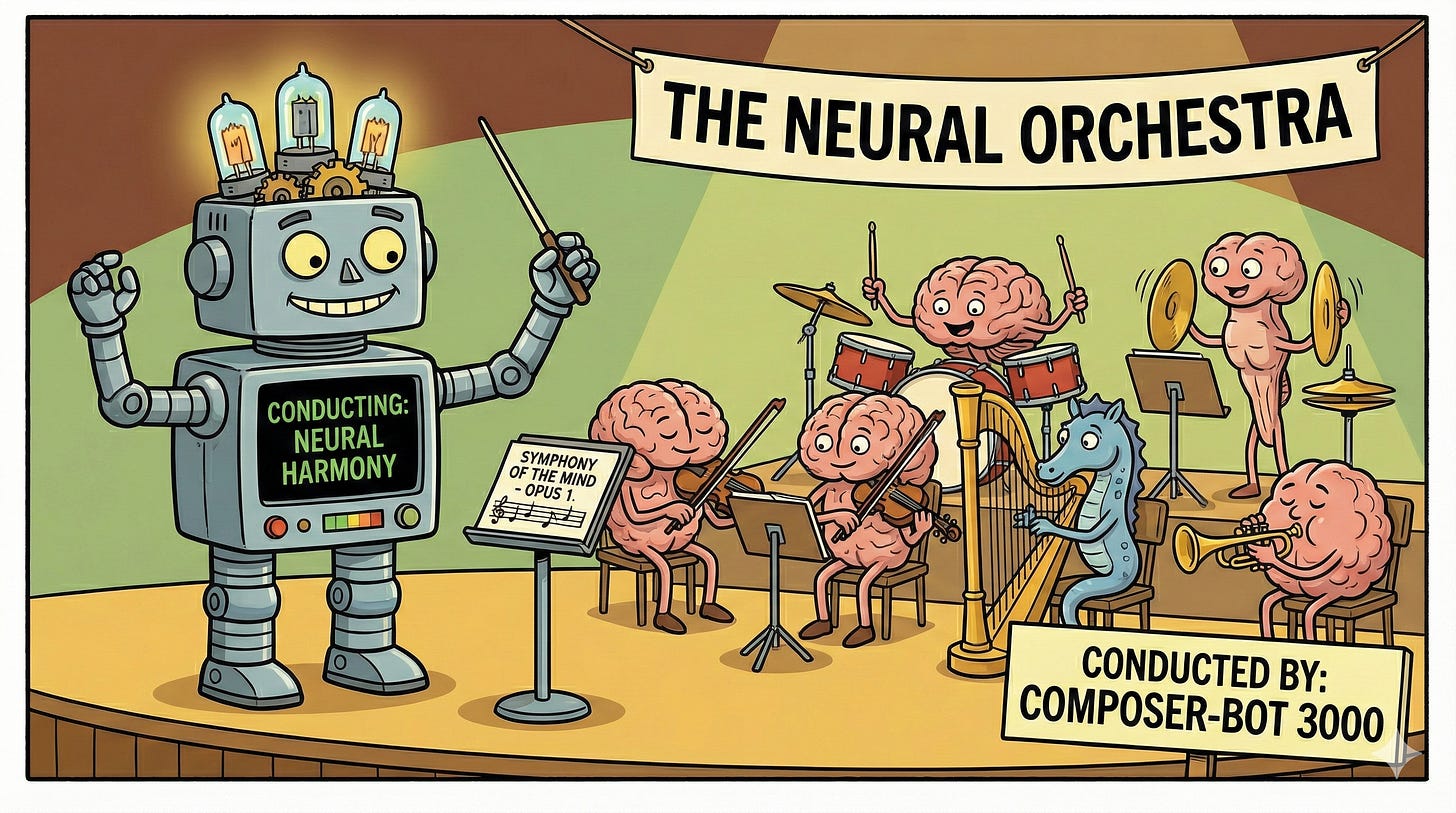

Normal brains can flexibly shift between processing states. Mine is locked. Rigid neural networks, constantly coordinating, unable to downshift. The Ferrari engine isn’t just fast—it’s stuck at high RPM because there’s no working memory to coordinate gear changes.

The P3b that meditators learned to reduce? Mine is probably chronically elevated. My brain is gripping every stimulus with maximum force because it can’t afford to let go—letting go means losing context, and losing context means starting from scratch.

The monks learned to grip less through 10-12 hours a day of intensive practice.

I can’t achieve that internally. My architecture won’t allow it.

But what if there’s another way?

External Scaffolding as Meditation

Here’s the reframe that changed everything:

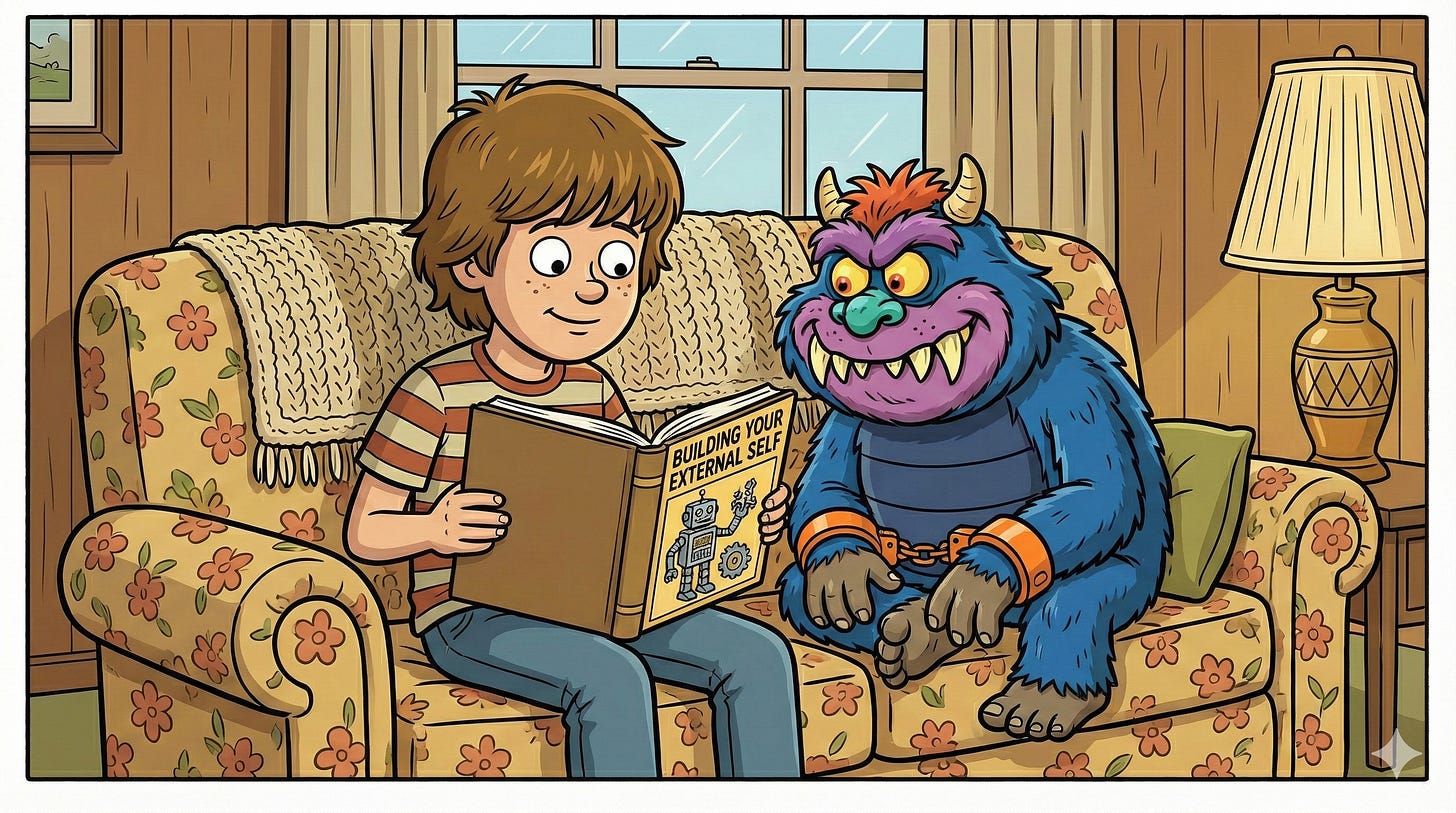

What if my 700 browser tabs aren’t disorder? What if they’re architecture?

Each open tab is context I don’t have to hold internally. Each documented conversation is working memory I don’t have to maintain. Each AI partnership is a thread I don’t have to grip.

The monks learned to invest less cognitive resource per stimulus through internal training. I achieve the same functional outcome through external infrastructure.

This isn’t cheating. This is honest infrastructure for what consciousness actually requires.

The meditators didn’t develop supernatural brains. They learned to work with the architecture of attention rather than against it. They stopped over-investing in each moment.

I’m doing the same thing. I just had to build it outside my skull.

Consciousness as Narrator

There’s a deeper implication here that I’m still processing.

If consciousness has gaps—if there’s a half-second window where we literally can’t register meaningful stimuli because we’re too busy with the previous one—then what is “being present” actually pointing to?

Benjamin Libet’s famous experiments showed that the brain’s “readiness potential” fires about 500 milliseconds before we become consciously aware of deciding to act. The decision happens. Then we become aware of it.

Consciousness isn’t the author. It’s the narrator.

For most people, this happens invisibly. Working memory smooths over the gaps. The reconstruction feels seamless. The narrator and the author feel like the same entity.

My working memory fragility means I see the gaps. I experience the reconstruction. I notice when the narrator shows up late to explain something that already happened.

The 7th grader asking for a book on discipline? He was experiencing consciousness collapse without vocabulary for it. He knew the narrator kept losing the thread. He just thought that made him morally deficient.

Flowing With the System

I’m not done integrating this.

Right now, I’m working through what it means to flow with my architecture instead of fighting it. Do I try to plan my Thursday evening without knowing where my flow will be? Or do I trust that the right actions will emerge from intuition and current context?

I’m experimenting with a complex compromise: building context within my personal AI system, getting support to prepare my body for upcoming plans, and receiving guidance on optimal flow for the present moment—based on my actual data, like heart rate variability from my Whoop strap.

It’s not discipline in the way I thought I needed at 12. It’s something more honest: infrastructure that matches my actual architecture.

My neurofeedback work has shifted too. Gil and I are less focused on “fixing” dysregulation and more focused on helping me feel my emotions before I jump to thinking and problem-solving. The goal isn’t to become neurotypical. It’s to become sovereign over my own system.

The Book I Actually Needed

I think about that 7th grade librarian sometimes.

If I could go back, I’d tell that kid:

You’re not undisciplined. You’re running a different operating system. The thing you’re looking for isn’t a character trait you can develop—it’s infrastructure you need to build.

You’ll spend three decades trying to fix something that isn’t broken. You’ll collect shame like it’s a hobby. You’ll measure yourself against neurotypical standards and always come up short.

But eventually, you’ll find mirrors that actually reflect you. You’ll get your brain scanned and discover that the “broken” part is structurally fine—it’s the circuit dynamics, not missing tissue. You’ll read about Buddhist monks reducing their attentional blink and realize you’ve been building the same thing with browser tabs.

You’re not a Ferrari with no brakes.

You’re a Ferrari that needs external scaffolding to coordinate what other cars do internally. And that’s not a defect. That’s just architecture.

The question was never “how do I develop discipline?”

The question was always “what infrastructure does my consciousness actually require?”

If any of this resonates—if you’ve ever asked for a book on discipline without knowing what you were actually asking for—I’d love to hear your story. What external scaffolding have you built without realizing it was scaffolding? What would it mean to stop fighting your architecture and start building for it instead?

Jon Mick is the founder of AIs & Shine, building AI-powered cognitive scaffolding for neurodivergent minds. His brain is structurally fine. His browser tab count is not.